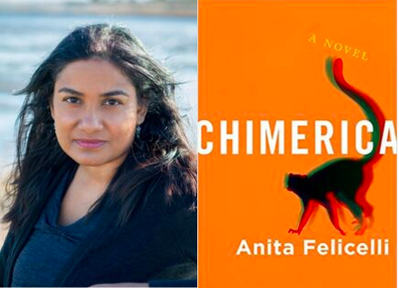

Anita Felicelli, author of Chimerica Anita Felicelli, author of Chimerica On May 6, at noon, live via Zoom (meeting links below), our premier guest Book Chat author is Anita Felicelli, one of two writers featured in our April virtual Stories on Stage Sacramento events (YouTube video posted below). Her novel Chimerica is, on one level, a legal thriller. The main character, Maya, is an attorney, as Anita used to be. And, like Anita, the novel is so much more than that. It’s an exploration of identity, of other-ness, the absurdities of the legal system, ambition, marriage, motherhood, and, of grasping and letting go. And then, there’s the lemur, a fully realized character. Chimerica is a novel the critics have heaped with praise, and, also struggled to categorize, which is why my interview with her, via e-mail, begins with a question of where Chimerica fits in terms of literary genre(s). S. It’s been interesting to read all the ways book reviewers have tried to categorize your novel Chimerica. For example, the LA Review of Books says “ANITA FELICELLI’S propulsive debut novel, Chimerica almost dares you to try to categorize it. A legal thriller that builds to a climactic courtroom showdown. A heist drama that pits two scrappy underdogs against a preening art world celebrity. A magic realist yarn with an eye-popping premise in an everyday milieu. True to the hybrid mythological creature referenced by its title, Chimerica is unapologetically and effortlessly all these things. But perhaps most of all, it’s a work of cannily revisionist California noir, a genre that, in Felicelli’s deft hands, somehow encompasses all the others, reflecting the world we think we know back to us in all its strangeness.” Other than being a terrific review, what do you think of this attempt to pin down the genre of your book? A. I loved this review; nobody deserves a review as smart as this one is, and it’s a gift to be read so well. I think it was extremely perceptive of the reviewer to look at the way the book plays on genre and hybridity. I was trying to tell a new story, one I’d never heard or read before — the story of an immigrant woman who has a hybrid identity, who fits nowhere and with nothing, who learns to tell her own life story by telling her client’s. There’s no existing genre to which her life conforms; she’s so alienated from her origins, she has to learn about them by reading blog posts. More than people who can take for granted that the structures of America will confirm their feelings and thoughts, Maya (the protagonist) is attentive to the stories other people tell and what stories might appeal to others like the jurors who hear the lemur’s case. She doesn’t have any of the power or belonging that people who neatly fit into categories have, and there’s no existing genre upon which to structure her life. What could be a disadvantage, perversely, gives her a bit of superpower as a trial attorney— she needs to read people and the stories they tell about themselves, so she can. S. So, do you think there even is such a thing as genre anymore? When writers are crossing all sorts of stylistic lines, and it seems like anything goes when it comes to novel and short story forms, do you think such categorization is necessary – or even possible, in some cases? A. Yes. Most books published by large publishers adhere to traditional genres. They have to adhere to some extent, in order to give the average reader a sense of what to expect from them when buying them. There are a few risk-taking publishers who understand we need radical form and cross-pollinated structures to accommodate new stories about America. The legal thriller, for instance, must be bent and changed for stories that don’t fully affirm the inherent fairness of the legal system. The cynicism of noir has a different valence when it takes on loneliness arising out of racism and discrimination in America. I don’t prefer categorization, but publishers, like every other industry, need to remain profitable to stay afloat. And enough readers are reading in order to satisfy their expectations that genre does matter. As a critic, I always try to remain sensitive to an author’s intent to bend or break forms in order to tell a new kind of story — the author as artist, rather than recipe-follower, but I read plenty of reviews in which critics are uncertain how to evaluate a book without the safety, predictability, and formula inherent in genre. S. Where did the idea for the character of the lemur come from? Once he showed up, did the intent and meaning of the novel change? A. The novel’s premise of a lemur coming to life from a mural was there from the start. The first intent of the novel was to explore the power of art — symbolized by a painted lemur coming to life — and the way in which copyright litigation in America, with its emphasis on enforcing ownership, fails to grapple with the essential freedom of art and all the ways in which art needs to call upon other art for its power. I wanted to write something along the lines of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings, but about America. The intent evolved with each draft. I came to explore what litigation or extreme competition does to the psyche, what inequality does to the psyche, how the process of assimilation to systems makes the person who truly assimilates a little less free, less original. It became fully a novel about a woman’s ambition, I think, but it began as more of an allegory with the lemur. As I went through drafts, I put Maya’s psyche on the page more insistently. In earlier drafts, she took the same actions, but her emotional make-up and her motivations were more opaque; with later drafts I focused on what emotions and thoughts might make someone take the actions she takes as a litigator and fused that with the allegory about the lemur. S. Maya is a woman of color, as you are. Do her experiences reflect yours? A. Somewhat. Many aspects of my personality are hugely different from hers and I was careful to incorporate those differences into what happens in the novel — her character drives the novel. Maya is aggressively seeking a conventional American Dream and a certain status in America, neither of which have ever interested me. She’s also fairly Machiavellian, she’s willing to suppress and abase herself to achieve that much-desired status within a prestigious firm; I’m not. I wasn’t a mother when I was an attorney, or even when I started writing Chimerica; as a working mother now, however, I feel certain I got her quandaries as an ambitious working mother of color at a law firm right. Those are the quandaries I would have faced if I’d stayed at a firm. As someone who buries her feelings and performs, Maya’s realizations about discrimination and inequality in America come fairly late — middle age! — while mine came in elementary school and are probably the very reason I became a writer; my own story doesn’t make for an interesting dramatic arc. S. When the actress Kat Miller read the selection from your novel at our virtual event, she was literally overtaken by emotion as she read the passage where Maya describes always feeling “other.” How did you react to Kat Miller’s response to your words as she read them? Were you surprised? A. I was surprised. You write novels in a complete vacuum and it’s not always clear how they’ll be received by people who don’t know you. I wrote the book for myself, wanting to write a book I wished existed in the world as a young adult, and I could only hope or dream someone would have the sense of emotional recognition that I long for when reading fiction. It was moving to me that she connected the way she did; I’m grateful. S. You were also an attorney, as Maya is. This adds to her authenticity on the page, of course, but unlike her, you left the profession. I’m curious about what it was like to shift abruptly from one type of work, which may have been a lifetime goal, to another, a life as a writer and teacher. A. It would have been difficult if being an attorney had been my lifelong goal, but I went to law school almost on an idealistic lark. I cared deeply about equality and justice and was naturally good at arguing different perspectives and I’d been writing and storytelling all my life. The spring before my senior year of college, I correctly understood law to be a practical application of those interests, but I discovered, too late, that my sensitivity and artistic temperament made it emotionally draining and tedious to do the actual work that needs to get done in litigation. Nonetheless, as an immigrant raised with a fear of failure and impoverishment, I persisted. Once I was a litigator with some experience, I found it even more difficult to extricate myself; it took me eight years to find an escape hatch. Nobody outside the law found it plausible that I wouldn’t want to practice. Still, eight years of practice is more than enough time to build up a strong identity and sense of responsibility as an attorney, and leaving practice, losing both the respect it engendered for the knowledge I’d accumulated and the satisfaction of helping others in a concrete way, was a little painful. I continue to carry a sense of ethical obligation from my time as an attorney, but I’ve now been a working writer and ghostwriter for a few more years than I was a litigator and I rarely, if ever, think about that earlier life. Chimerica exorcised it. S. As a working writer, you write reviews, essays, commentary. You’re an active part of your literary community. How important do you think it is for a writer to be a good literary citizen, especially now? Do you think the place of the writer has changed during this time of shutdown? A. I think it remains valuable to be a good literary citizen, but we don’t all have equal flexibility during the pandemic. There’s homeschooling, altered work hours, reduced finances, the need to process the fear and other dark emotions of this experience. All of that takes time and attention and reduces the wherewithal to be fully present for others. I write fiction in part to relieve the drama of my internal conflicts and need to carve out time to do that as well, even when it’s going poorly. I imagine some other writers feel this way, too. I think being in community with each other necessitates we have empathy for the enormity of this experience, however timeless plague might be, and the changes in what each of us is able to offer. However, I’m so amazed at the generosity and literary citizenship of all of you at Stories on Stage. S. Thank you. It is entirely our pleasure, especially when we have a chance to present such a complicated, fascinating work as Chimerica.

Sacramento writer, Sue Staats Sacramento writer, Sue Staats Sue Staats is a Sacramento writer. She directed Stories on Stage Sacramento for six years, from 2013 to 2019, and now contributes interviews and blog posts to the website, and cookies to the events. She’s currently looking for a home for her short story collection and getting her feet wet in a couple of other projects, with the hope that eventually one of them will draw her into deeper waters. Sue's fiction and poetry have been published in The Los Angeles Review, Graze Magazine, Farallon Review, Tule Review, Late Peaches: Poems by Sacramento Poets, Sacramento Voices, and others. She earned an MFA from Pacific University, and was a finalist for the Gulf Coast Prize in Fiction and the Nisqually Prize in Fiction. Her stories have been performed at Stories on Stage Sacramento and Stories on Stage Davis, and at the SF Bay-area reading series “Why There Are Words.” Topic: BOOK CHAT--ANITA FELICELLI, CHIMERICA Time: May 6, 2020 11:45 AM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/85125307558 Meeting ID: 851 2530 7558 One tap mobile +16699006833,,85125307558# US (San Jose) +12532158782,,85125307558# US (Tacoma) Dial by your location +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 929 205 6099 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Germantown) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) Meeting ID: 851 2530 7558 Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kPXbyT2g

0 Comments

|

|

Who We AreLiterature. Live!

Stories on Stage Sacramento is an award-winning, nonprofit literary performance series featuring stories by local, national and international authors performed aloud by professional actors. Designated as Best of the City 2019 by Sactown Magazine and Best Virtual Music or Entertainment Experience of 2021 by Sacramento Magazine. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed