|

By Sue Staats

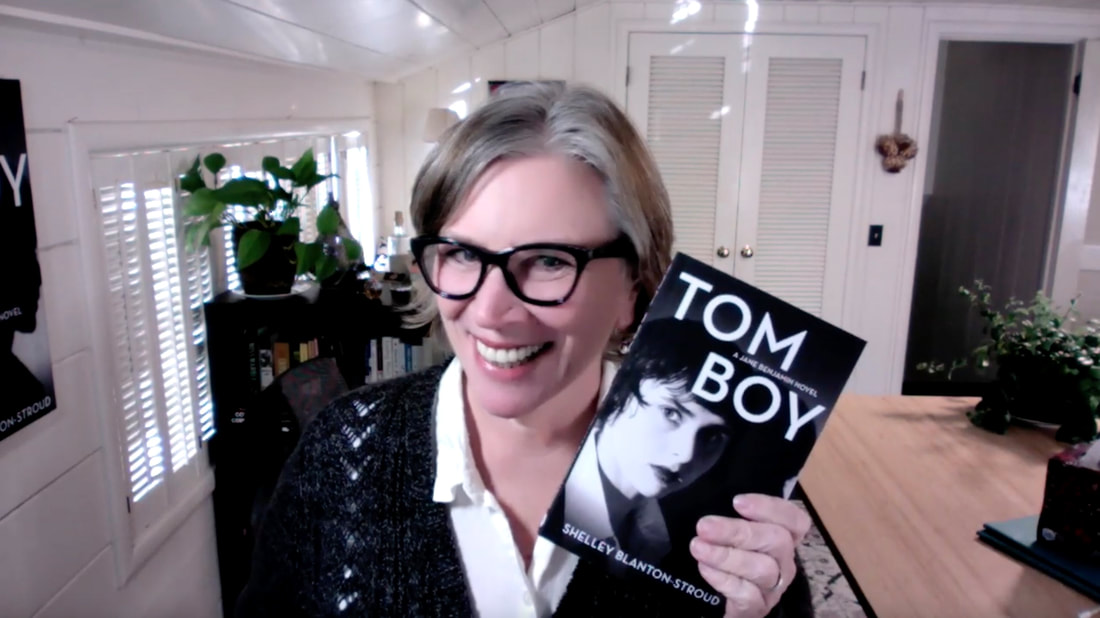

In Shelley Blanton-Stroud’s second novel in the Jane Benjamin series, Tomboy, we find our heroine chasing her dream of becoming a gossip columnist, sailing to England on the Queen Mary, wearing glamorous evening gowns and, of course, solving a murder. What in the world has happened to the scrappy, boyish reporter wannabe and crime solver we grew to love in Shelley’s first Jane Benjamin novel, Copy Boy? To get at the heart of Jane’s transformation, Shelley and I dig into the gritty background of this tough survivor who’d rather wear trousers, and I discover that creating such a character is part family history, part Herb Caen, part research elves at the Sacramento Railroad Museum, and a generous dollop of that well known potion, Bad Girl Juice. Sue. Jane Benjamin is such an interesting character. We meet her first in Copy Boy, were she has to pretend to be a boy to get the lowest job on a newspaper. In Tomboy, she’s a cub reporter, chasing her dream job. When I first met you, Shelley, in that Community of Writers workshop long ago, the protagonist of the novel Tomboy was quite different. So, how did Jane Benjamin evolve? What inspired her? Where did Jane Benjamin come from? Shelley. Part of Jane comes from my father’s impoverished childhood, living in a tent by the side of the irrigation ditch, having to do things no child should have to do. He’ll tell you that those experiences created the grit that allowed him to accomplish so much, a boy who read Zane Grey novels in an outhouse far from his family’s tent, who then rose to become superintendent of schools. But I don’t know. I think that gritty experience can also shave off some of your finer things. So you gain and you lose by becoming gritty. I wanted to explore a protagonist who is tough and survives and keeps going, because I admire that. But I also wanted to recognize that she doesn't always make ideal choices, because her her drive to survive. That’s inspired by my dad. But another starting point was Herb Caen, (the long-time columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle) our own Sackamenna Kid. At the workshop where we met, I brought a chapter from my first version of the novel, when Jane was a young Herb Caen. A couple of the young men in the workshop pointed out that in the scene where Herb meets a beautiful young woman, I hadn’t dealt with his physical attraction, what would have obviously been his erection. They asked why I didn’t go into into how aroused he felt at being around this young girl. And at that point, with it being my first novel, I thought, I'm not up to this yet. So I turned the character into Jane. Sue. You’ve just answered my next question, which was why you made the character female. I think it actually makes her better, as she has to overcome more to get what she wants. But I’m also wondering why she wants to be a gossip columnist. She’s such a complex character, and it seems that her career aspirations aren’t really worthy of her talent and intelligence. Shelley. Oh, I have so many reasons for this. One is that if you trace the life history of women who were, let's say, successful old women in the 1980s, and you went back and looked at the work they had done over their lifetime, you would find they very often did work that was below them. Why? Because that's the work they could get. I mean, I was so moved when I learned how Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor graduated at the top of her class at Stanford Law School class and couldn't get a job as a lawyer. She worked as a legal secretary. She shouldn't have had to. It was below her. But she did it in order to grab her first spot on the ladder. Women of Jane’s time period, the 1930s, weren't stepping right into what they deserved. They took what they could get. And the truth is, gossip was something Jane could get. They would let a girl do gossip, and they would pay her pretty well, as they did Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. Something else about Jane is that she's annoyed when people think it's below her to do gossip, even though she's feels it's below her to do gossip. You know what I mean? And she's going to aim to do better things, mostly in secret, where she'll never get credit for it. She's ambitious. She wants it all. She wants it all. Sue. You use the word “difficult” to describe Jane. And I would say Jane is more than difficult. She’s a bad girl. She is unquestionably morally compromised, she does what she has to do to survive and to get what she wants. I was a little bit horrified at some of the choices she made in Copy Boy, and in Tomboy. I’m wondering why she’s like this, and how do your readers respond to a character who does right things for the wrong reasons, and also wrong things for the right reasons. Shelley. That's a great question. I get a lot of different reader response. I have a friend, a reader who's a man, and he's a little worried that I'm doing this with Jane. He would like her to be better behaved. And you know what, he is very well behaved. And also, the women he likes are very well behaved. So I get that he wants Jane to be someone whom he would have over for lunch, right? I get that. But also, there's a part of me that writes these books for myself. I spent 34 years teaching while raising children. But now I am writing for me. I want to keep learning, stretching, trying things. Even if they don't work. I want to take some risks. And one of those risks is to let a woman be something of an antihero, like so many successful men have been. For example, if you watch almost any of the HBO series featuring men, they are morally compromised. They make all kinds of bad decisions. Take Deadwood—oh, my God, that main character, what an awful person. And I was rooting for him at every turn. We're watching Peaky Blinders right now. Same thing exactly. I think young female readers have the kind of response I'm going for. Their reviews keep using the word badass. Sue. Oh, I agree. You’re absolutely right. And I see there's a lot of exploration going on, as you create Jane and she continues to evolve. How much of you is in the character of Jane? Shelley. Oooo! My answer to that question would be no, I'm not Jane. It's more like Jane’s my dad, right? While I'm the library girl. I sit around reading books. I'm so sedate. I don't take risks. I don't break rules. I’m a good girl. I’ve lived my life as a“good girl.” But you know what, Sue? That's not everything going on in my head. I chafe a bit against the expectations. And I have a feeling of comradeship with characters who chafe against the expectations. That's part of Jane for me. It's not that I really want Jane to be an antihero in the same way Walter White is, in Breaking Bad. It's just I want the opportunity as an aging woman to explore her as appealing beyond civility. Can a compromised woman also be in some way heroic? We'll see if it pans out. Right? Sue. Oh, I really encourage you to do that. I think a lot of us who have lived lives as good girls are full of that bad girl juice that’s just dying to come out! Shelley. Can I use that phrase Bad Girl Juice? Sue. Absolutely, but you must give me credit in your next novel! I wanted to talk about another aspect of Jane that’s unusual, and that is, she pretends to be a boy. She prefers men’s clothing. On your website (here’s a link: https://shelleyblantonstroud.com/) you’ve posted several excellent interviews you’ve done with magazines and online journals. One especially interesting one was with Girl Talk HQ in which the interviewer assumes Jane is gender fluid. In the 1930s, Jane’s considered a tomboy, which was seen differently then, than today. Did you intend for Jane to be gender fluid? And how do you deal with the modern assumption that a woman who dresses like a man secretly wants to be one? I don’t know if you intend this for Jane or not. Shelley. Only just this morning, right before I turned on Zoom for our talk, I was answering interview questions from a writer who asked, Just literally, what is Jane? Is she bisexual? Is she lesbian? Is she trans? She wanted me to put Jane in a bucket. It reminded me when I taught Death of a Salesman, and my students asked, Does he have Alzheimer's? Schizophrenia? You know what I mean? They wanted his medical condition, in order to interpret him. I have investigated real life people's response to questions about their sexuality and their gender. And I have always been most interested in those people who say, I cannot be pinned down so easily. There's a nonfiction book called Tomboy: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different, by Linda Sellin Davis. Her own daughter calls herself a tomboy. And she defines it as I like to wear boy things. I like to play boy ways, but I'm a girl. Obviously, I'm a girl, her daughter says I am your daughter. Davis researched how individuals felt about their gender and their sexuality. Turns out a good number of people just want to be who they are the way they want to be at any given time. And then they want to be free to change. And I sort of expect that of Jane. I'm envisioning her as someone capable of being many people and capable, ultimately, of loving many people. I think she will have sexual experiences with men and with women. I think that she'll be capable of feeling good about both. I also think she can wear a dress. But she really enjoys dressing in the comfortable way of men in her time, because she can get more shit done that way. Right? So I guess you would have to say, she's gender fluid, you know, if it helps readers to put her in a demographic box. You might also say she's bisexual. But I'm not sure. I’m not done writing about her yet. Sue. You’re going to have to deal with all the social norms she encounters as she moves through time, in future novels. That’s going to be a very interesting bit of research for you to do, Shelley. Shelley. Yeah, it's part of the fun of it. Sue. Those articles you posted were a treasure trove. In another one, you again mentioned the specific experience your father had that inspired you to write Copy Boy. He was young, his family was very poor, migrant farm workers, and he had to do something awful. I'm wondering if you could share that specific story. Shelley. The event that precipitated all this, was the 75th anniversary of Grapes of Wrath’s publication. NPR got a playwright, a painter and a filmmaker to travel the Joad family’s route, ending in Bakersfield, where I was raised. And at an event at Cal State Bakersfield, a historian was to interview my father on stage, because his family had traveled that route, and landed in Buttonwillow, ultimately in Bakersfield. They had lived at the Hooverville that is described as “Weedpatch” in Grapes of Wrath. The night before the event, we gathered at my aunt Penny’s house. My dad was one of 10 kids, and all his siblings were there, and their kids and so on. Aunt Penny and my aunts made us this amazing meal, you know, I mean, she even put cotton stalks on the table (because they’d picked cotton.) She had my granny's old quilts on the table. There were baked beans and fried chicken and biscuits. And at the end, we sat in a circle talking, and the eight boys and two girls in that family. They all wanted to know what my dad was going to say on stage, because they were going to go to this event. Their family motto was, Don't embarrass the family. When you have so little, it's important to protect your dignity. Don't embarrass the family. So they were telling all these really funny stories, because the Blantons are funny. They're very funny. And then there was a silence. You could see my dad's face getting redder and redder, and he said, You want me to tell the good stuff. I'm telling the truth. His siblings were not happy about that, because his version of the truth wasn't their version of the truth. So we go to the event. He’s on stage, and he tells the story about how when he was, I think , 12 years old, and living in this tent, and his best friend is in the tent next door and they're playing outside. You know, my dad's family has all the kids sleeping in one bed, so you are outside as long as you can before you have to go share a bed. So the two boys are playing marbles or something in the dirt, and his friend’s mom comes out of her tent and says I need you to get rid of Daddy. Well, his friend’s father was a drunk. And when you're living on pennies a day picking cotton, when even the children are picking cotton before and after school, this isn't just Oh, he's a drunk. This is, He’s going to kill us by drinking the money. So my dad's friend was crying and upset and couldn't do what his mother asked. So my 12 year old dad took the car keys from his friend’s mom, and the friend and my dad dragged the friend’s passed-out father into the backseat of the car. And my dad, who didn't know how to drive, drove an old jalopy 30 miles down the road to just about Shafter, I think. And they pulled the friend’s dad out of the car and left him by the side of the road. The whole drive, the friend’s dad is crying, sobbing, begging, the friend is crying, sobbing, begging. But my dad pulled the man out of the car, and drove his friend back to the tents, and went back to his tent to sleep. The next morning, his friend’s tent was gone. And my dad never saw him or his family again. He told that story on stage, a story his siblings did not want him to tell. And he said, I tell you this because you cannot know who I am without knowing that I did that when I was 12 years old. So that story is in me. It did not happen to me. But like with epigenetics, the way that you can inherit someone else's experience, it is in me, and it clogs up my lungs, making it hard to breathe sometimes, because I lived with that story. When my father delivered that story on stage, I saw that playwright with the NPR crew lean forward and start writing down every word. And I thought, Oh, my God, he’s taking my story. And that's when I began to really write Copy Boy in earnest. It wasn't that the playwright couldn't use it, it was that if I wanted to use it, I needed to use it in my way. Sue. Wow. It’s one thing to read this as the act of a character in a novel, it's another to hear it you tell it. It’s kind of in my lungs, too. Wow. And of course it changed him. It was something no child should have to do. Shelley. When my dad interprets himself, he hates that he had to do that thing. But he's also proud that he did it because he feels it made it possible for that family to go on. Sue. It’s a terrible, terrible choice. And it’s one, that, in Copy Boy, Jane has to make. So that explains why she does things and makes decisions that a reader who's never had to be in that situation would think of as morally compromised. Let’s change gears a little bit. Tomboy, like Copy Boy, contains a crime. Someone’s murdered. So the novel becomes about solving a crime, as well as Jane’s effort to get what she wants. Did you start out writing this as a mystery, or did it evolve? How did mystery creep into the Jane Benjamin stories? Shelley. Well, Copy Boy took me 10 years to write. And that's because I was writing things I was thinking and feeling and remembering and wanting to explore, but it had virtually no structure. So there were a lot of drafts. Finally, when I was talking to a reader, she asked me what I was going to say happens in this story. And I realized I didn't even frame it in terms of a plot or a shape. As a teacher, I loved trying to figure out what things mean. Then trying to map out how to reveal meaning for my students, or how to provoke them to find their own meaning. I spent 34 years doing that. And, that's what a mystery writer or a thriller writer does, they try to figure out what they think something means, then they try to figure out the method by which they can reveal it or provoke the reader to find their own revelation of that. It gives the story a shape, often relying on an archetype. Almost like the formal poetry structures, where a poet can find all kinds of creative freedom within the structure. The shape of the mystery story, the thriller, gives me the shape, the structure, to explore the things I want to explore. Sue. And then there’s research. As a writer of historical thrillers, you must have to do a ton of research. I imagine that’s something you really like to do, and I’m wondering how you avoid going down the incredibly tempting rabbit hole of research, and never getting to the writing. How do you structure your time so that you do the research you need to do, and also , the writing you need to do? Shelley. Well, someone recommended writing the story and the characters first, then going back and doing the research in the context of the story. I tried that with Tomboy, and it didn’t work for me, because I get inspired by the little nuggets I find in research. As an example: I couldn’t go ahead with writing Tomboy. I wanted to Jane to move ahead in history, and I was very, very interested in women’s ambition. And I think there's no more explicit place to explore female ambition than in sport. And the only sport I could picture where a woman's stakes would be high enough, where failing and winning would be significant enough to make scenes play on it, was tennis. One of my readers, Carolyn Martin, said, well, you need to research Alice Marble, who won the 1939 Wimbledon championship and was from San Francisco. I learned, reading her biography, about the relationship between Alice Marble and her long-term tennis coach, with whom she lived. And finding that history is what broke everything open for me for writing Tomboy. The book isn’t about the tennis player and her coach, but it revealed to me what I wanted to have happen in the book. The research is inspiration. But then you have to keep writing the story, and developing the characters, and then go back for historical details, that will flesh it out more fully. Sue. You must have to really discipline yourself so that you don't get too lost in the research before you get into the writing. Do you consider yourself a disciplined person in that way? Shelley. By nature? The opposite. I'm a sloth. Absolutely. But every morning I get up and fight my essential nature. I calendar myself, not because I think organization is better than looseness, but because there are things I want to do, dang it! And it's not like time is infinite. I want to write, not because it feels like work but because it feels sometimes like the biggest joy in my day. So it’s worth the discipline. But about the discipline of research? I’ve had help. In Tomboy Jane needs to get to the East Coast to catch the Queen Mary, to sail to England. I didn't know how to get her there, and I was kind of rushed, and exhausted. So I sent a note to Chris Rockwell, who's the librarian at the Railroad Museum, and asked if there was anyone I could talk to about how to do this. Two weeks later, I got an email back. He’d put two volunteers on it. And they came up with a 19-page single-spaced document called Let's Get Jane to New York. There was every train route. Her best price options, what a newspaper would be likely to choose. Where the rich people would stay on the train. Where the poor people would stay. How food would work, what the upholstery was like. The sandwich Jane eats on the train, I got from that document. I learned much more with Tomboy than I had known with Copy Boy, that it's possible to reach out to friends or connections to ask them a favor, they can reveal what you need. In another case, I was struggling with what kind of effect a concussion would have (in Tomboy, Jane suffers a concussion.) A very good friend, Dr. Beth McClure, really checked in on things and adjusted them and showed me where emotions would be different in different times of the story arc. So, you have to do your basic research, but then reach out to people about their experience. Sue. I had a similar experience with the Railroad Museum for a project I’m working on. They’re the best resource nobody knows about! About that concussion. Doesn’t Jane have enough trouble, without her author giving her a concussion, too? On top of everything else? Why did you add another layer of difficulty, when she’s already struggling with plenty? Shelley. It actually goes back to the very first page, to her responsibility for her baby sister. I wanted to make it clear from the beginning that for this difficult girl, caregiving of her sister was doing her harm. And I wanted it to be kind of literal, that she is hurt by caregiving. But still, the caregiving is worth it. Right? But she is reckoning with the fact that she experiences losses and trouble related to giving care. And you know how you choose one thing (Jane’s baby sister accidentally bangs her head against a wall) and then, you know, to use the boat metaphor, you make a slight adjustment right here, and then all of a sudden your boat is sailing to a different country. And that's kind of what happened. Because I did that, then the concussion became something. Sue. Right. It becomes incredibly important in what happens to her and how she's treated and what she does, and the effects of the concussion starts to really drive a lot of the action, along with all the other things that are happening. Sue. Let’s talk a little bit more about you. I want to know what sparked writing for you. How old were you? And what was your first story? And do you still have it? Shelley. I always pictured myself my whole life as a reader, not a writer. I was an avid reader constantly. I mean, just that was my activity. It probably would have been better if I learned about sports at a younger age. But I was always a reader. That's how I pictured myself. Then, when I was about forty-nine, my husband Andy and our sons were on a scuba diving trip. I was heading off to a library book talk when I got a phone call from the Monterey Bay Ambulance Company and as I answered I thought, which one is it? My husband or my sons? But it was my oldest son, and he said everything was okay, we're in an ambulance. Dad's had heart failure in the bay. And so of course, I drove there like crazy, He's fine now, but after that we had some conversations about the fact that if there's anything that we want to do, we really ought to do it. And I had to do some excavating. And I realized that after all this reading and talking about books I've done forever, I kind of thought I could make one or two. And I wanted to try to do that before my time was up. That’s what started the process. So I signed up for a flash fiction workshop led by Valerie Fioravanti. I thought it was a good place to start. Not too overwhelming. And on the second class assignment, I wrote a flash piece that I care very much about, and it's called “Birthday.” I submitted it immediately after to a website and they accepted it. It’s about the day that my first son was born and died in a day. It was the first time I had written down what happened, and also my impressions of what had happened, the weird little impressions I had that weren't quite right. You could see my disjointed thinking and emotions. It was under a thousand words, and it was about the most significant experience in my life. And it happened in this little workshop on the second week, so I kind of love that. That's my first beloved short story. And thank you to our first Stories on Stage Sacramento director (and founder,) Valerie. Sue. This is the second time your work has been featured at Stories on Stage. What’s it like for you, hearing your work read? Shelley. The first time, Jessica Laskey, our current casting director and future program director, was the reader. The story was meant to be a chapter in the novel I was writing about a tennis player, that turned into Tomboy. Sue. And I remember you saying to me, this chapter is gone, it’s not even in the book anymore. And I remember saying Shelley, I don't care. I really love this story, we’re using it. Shelley. That’s right! At the reading, I had no idea what to expect. I felt so inexperienced at all of this. And it was so moving to me. One of the great things about becoming an author, at my age, you know, is that the sheer joy of every thing. The first time I saw someone perform my story, I was giddy. It was just sheer joy, because I didn't have to read it. I did not have the stress of wondering if I did my own self justice. Instead, I could watch this really talented, vivacious person spin it her way. I loved it so much, and that’s part of why I was really interested in Stories on Stage, and when you were ready to pass the baton, I wanted to accept. Because the experience I had as a writer was just joyful. It really was. Sue. My very last question to you is about Jane, where she lands next. World War Two is on the horizon, right? Things are happening. You give some hints at the end of Tomboy, that some of the characters might continue in following books. So I'm wondering, what's next for Jane? Shelley. Well, Book Three is tentatively called Flyboy. It takes place at the Richmond Shipyards, over five days in 1942. As a gossip columnist, Jane’s working with the Office of War Information propaganda group, trying to find a Winnie the Welder poster girl among the first five women granted boilermaker union cards to build liberty ships. Naturally, bodies start to fall. Sue. I love it already. And of course, I can imagine the poster as the book’s cover! Congratulations, Shelley: you’ve really created a fine and complex character in Jane Benjamin, a modern woman from the not-so distant past, and I can’t wait to see what she does next!

0 Comments

|

|

Who We AreLiterature. Live!

Stories on Stage Sacramento is an award-winning, nonprofit literary performance series featuring stories by local, national and international authors performed aloud by professional actors. Designated as Best of the City 2019 by Sactown Magazine and Best Virtual Music or Entertainment Experience of 2021 by Sacramento Magazine. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed