|

By Sue Staats

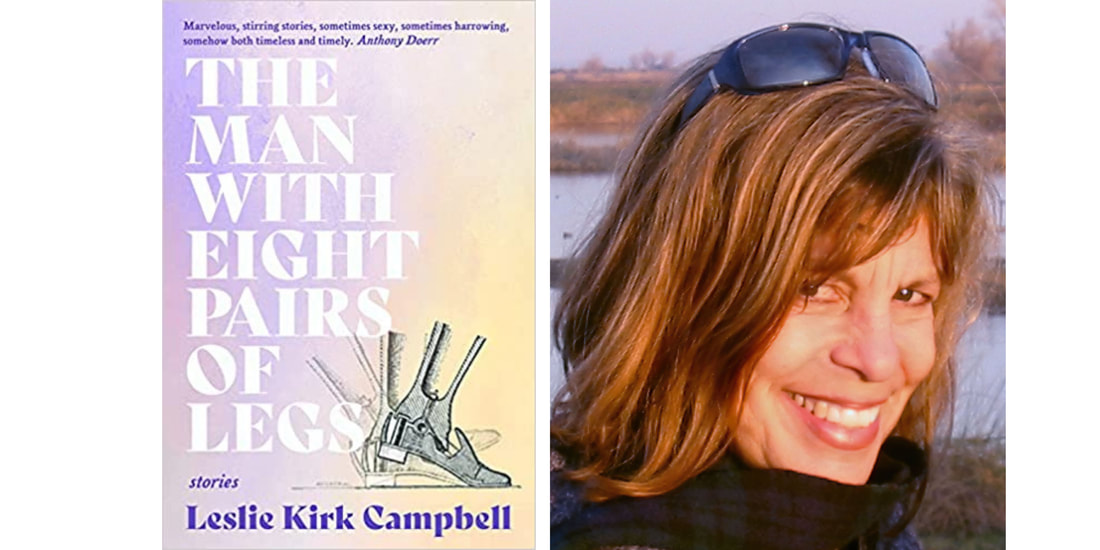

Leslie Kirk Campbell packs a lifetime of experience in her writing. Her first collection of her first short stories won the very prestigious Mary McCarthy prize, but it’s no fluke. She’s actually been a practicing and teaching literary artist for a long time. I met Leslie in a writing workshop six years ago, and it’s a thrill to congratulate her on her success, and to talk with her about her long and interesting road to her stories’ creation. Sue Leslie, congratulations on winning the Mary McCarthy prize and the publication of your debut collection of short stories, The Man With Eight Pairs of Legs. They’re spectacular, and I wanted to ask you about them as a collection. On the surface, they appear to be very different —different characters, different settings, different topics. And that makes me wonder why you chose this epigraph from Thoreau - I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound has become strange to me. Leslie Good question. Well, a couple things about that. First of all, I’m new to fiction. And it’s important that after about 20 years of teaching, creative writing and raising my two sons, and then a hiatus from writing poetry, I got into fiction. And there were these different ideas which were percolating or fertilizing quietly in my mind and my heart during those years, and when my kids were older and I went and got my MFA in my fifties, I wrote the stories that had been rummaging around inside me. Some of the ideas I’d been carrying along with me for fifteen years. In a long article I wrote about how stories gather, I talk about how I had trouble finding common themes, and I needed to have that to create a book. Michelle Wilson from Tin House, in a one-on-one, saw through it, because she had looked at the whole manuscript, and said, what about the body? And I realized that my body, which has, over time, been assaulted, violated, cut into, broken, birthed two ten pound babies… I’d danced, was a varsity track person, and my body had been talking to me all that time through all these different stories. In each of the stories the body has been marked by memory, often visibly and sometimes invisibly, through generations. There was something about the body in all of them. Women’s bodies, the violation of women’s bodies, but so many of them. There’s heroin tracks, the hermit’s tattoo, there’s bruises, scars, and there’s hyper-awareness in the character Harriet, in the title story, about her body. She can feel the circulation of her blood. And it’s also related to how I feel like a spiritual person. And the bodies are strange. I felt the combination of awe and strangeness. I loved that combination. Sue Where do your stories start? What’s the main point of entry? Is it a detail of place, an object, a scrap of dialogue, or something else? Leslie Oh, it really varies from story to story. I have no rules, and rarely any repetition. What I do see a lot is that there’s a visual image. For example, “Nightlight” started with a dream with a very strong visual image of a middle-class man and a homeless kind of wreck of a man, a younger man with their arms around each other, walking down the street away from the middle-class neighborhood, with the sun rising, and the wife of the middle-class man seeing them out of her bay window. And I wondered, why did the man leave his family? For the title story (“The Man With Eight Pairs of Legs”) I saw, in a TED talk, a photo of a whole row of these amazing prosthetics, they had all sorts of accessories, and that inspired me to think about what makes us human in a world of technology, when we can change and alter ourselves. There’s the whole question of enhancement, replacing bones, and even organs. Who are we anymore? Another example is “Tasmanians.” For that it was a sound in the street of someone cutting down eucalyptus trees. I was at my writing convent, where I go often, and I walked up the street and saw all these eucalyptus on the ground. I could hear the Spanish speaking guys who were cutting the trees, and I saw this woman in the driveway and I felt she was so sad, and that led me to say, why is she so sad? And then I discovered my character Mariam, with her skin feeling all the sins, all the pain of her grandmother’s experience of genocide and the march to Syria, from Anatolia in Turkey. And “Thunder in Illinois,” in that case it was the situation. I had this idea of a long-married couple, and could I make a story where they were playing a word game that went on for three hours, that could have a much deeper realization and deal with far more than the game. In general, I’m very visual, very sensory. The way light looks, sounds, smells, all those things are so important to me. And within each story: now I’m in the room, now I’m in the church, I always want to get that place. Sue You look around. What’s there for the character. What they see, what they smell. Leslie Right. And I’m also fascinated by unusual pairings of people who find intimacy or meaning, also pairing unusual characters with unusual stories. I want myself and others to experience this wide variety of people, whether it’s with a disability, or a woman who’s been beaten, or a woman invisibly suffering from ancestral inheritance, of genocide, in one case, whom nobody can understand. Sue I wanted to ask you about the stories being read at the event. We’re reading two, which is unusual, both because they’re very short and interestingly different. The first one is called “City of Angels,” and it features two young teens on their weekly trip to the Santa Monica beach. I'm wondering if you drew on your younger self for any of this Leslie I very much did, in that particular case. I was once one of those girls. I fictionalized a lot about it, but the memory of that place and time is something I experienced in the 60s. And that’s an interesting story: I was in an improv class recently, and they asked us to let our bodies discover movement and I found myself moving my arm in a particular way, and then they had us write. And what came up for me is that setting. There’s so many smells, so much light, and it all came to me in vivid details. And then I discovered the story of what that meant to the narrator, and her best friend. But the place, and those kinds of kids, definitely came from my memory. Sue The other story we’re reading, “The Hermit’s Tattoo,” is extremely different. It’s about a priest, who’s either crazed or an ecstatic… Leslie He’s a monk. Sue A monk. Whose remote cabin is swept away by fire. He’s also trying to eradicate his former self in a particularly damaging way. And I'm wondering where this story came from. Leslie This is an example of one that is completely fictionalized, although I did go to a hermitage up in Sonoma, to write. And Michelle Wilson, whom I mentioned previously, said you need one more story. And while I’d been working on the other stories for five or six years, I wrote “The Hermit’s Tattoo” that weekend, at the hermitage. I just used what was there, the setting, my image of this one man who I saw for about ten minutes. I came up with this idea of a man who’d been marked by a girl. He’d had this relationship that wasn’t sexual at all, was just early love and when she died, he had her name tattooed on his body, which he wasn’t supposed to do—he was supposed to forget everything, to remain clean for God. So it’s about his struggle between his love of God and a more human love. He’s just trying to get rid of it, as the fire approaches. It’s like, dreaming, and the little elements that happen gather together in your dream. They weren’t connected in real life, but they connected in the dream. Sue I love the end of that story, how he can’t erase the tattoo, and how the earth regenerates itself after a fire. Leslie Well, it sort of goes along with the whole thing, that the past never goes away. That damage can be done, and out of the damage something better can come. So, I thought he always realized that it (the tattoo) is always going to be there, and that’s okay. That it isn’t really part of godliness, but that they can coexist. Sue I want to talk also about the story, “Tasmanians,” which we're not reading but which you workshopped in 2016, at the Napa Valley Writers Conference. That’s where you and I met, in a workshop led by Yiyun Li. When you learned you had won the Mary McCarthy prize, you emailed all of the workshop contingent and I was really struck by what you said, that you’d been devastated by the critique you received, that it forced you to completely rethink the story. I wish I could find my copy of the story, so I could compare it to the published version, but I can’t. So I'm wondering if you could go over what happened, what the problem was and how you changed the story. And maybe you could talk a little bit about the agony of revision and the painful process of making a story better. Leslie I have to say that I don’t find the revision process painful. But as far as the story goes: people had said for a long time that I couldn’t have the gifts (the protagonist stores family possessions she receives from her mother in a hall closet) and the trees (a eucalyptus grove that surrounds her home) in the story. And basically, as a writer, I just had to work it out. When people tell me I can’t do something I get all worked up, and ignited, and motivated to do that very thing. At our workshop, the combination of what people were telling me was really upsetting. I felt they just didn’t really like the story, and I went to the winery event that night and I do remember crying in my car afterwards (laughs.) But it was a momentary crash that didn’t last that long. And one of the results was that I did take out a character, a housekeeper. And the result was that Mariam had much more agency and became stronger. But I want to say that I really appreciate the power of the workshop, and how sometimes it’s hard to hear certain things, and that the biggest thing that has made a difference is taking things out completely, like a character, or an idea, or two or three scenes , so that the story is leaner and has more intensity. And out of that I’ve made these stories much stronger Sue Oh, I completely relate to people not understanding a story you find very clear and getting very angry and upset. I get what you’re saying! Leslie And then I get a letter from Anthony Doerr, about the story “Tryptich” that I’d workshopped with him that I couldn’t believe. It was a page and a half, very specific about how much he’d loved that story in different ways. What a treasure. Sue You know it’s funny. I’ve been reading your story collection and Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land at the same time and I kept conflating the characters. I don’t know if that’s a compliment or not but I just felt your characters were that good, that closely observed. So there’s a similarity between his writing and yours. Leslie Well, clearly we jibed. And I love all his work. Actually it started with the short stories. Because he cares about language. Sue Well, you could not have a better fan of your work. Leslie Yes, it’s awesome. Sue In the blurb he wrote for your collection he said, “Here is writing that means something, that increases empathy in the world.” What do you think of that? Is “increasing empathy” what you were after? Leslie Well, my answer is yes. I feel like I’ve been put here on this earth to learn compassion. And I teach compassion as one of the six qualities of great writing. And I tell all my students that the most powerful thing you can do is let go of your ego and listen to each other. And I find that everyone suffers, everyone has suffered, and it's important to imagine ourselves in other people's shoes in l life, in general. And I feel that it deepens who we are, and as writers it deepens what we can give to our characters. Sue Let’s talk a little about your writing life. Because I was surprised at how long you've been a writer and how many literary forms you have been published in, and that that this is a debut collection of fiction, and also to find out you've been writing and being published since the 1980s. And that you founded and continue to run the San Francisco Creative Writing school, Ripe Fruit. When did you start writing? What made you consider starting Ripe Fruit? How did you evolve into fiction? Leslie Okay…here’s the short story, not the novel. As a child, I started writing poetry and fell in love with language. In high school for creative writing, I did poetry. At university, I did poetry. I had the amazing fortune of working with Scott Momoday at Stanford, and he was very encouraging about my poetry there. I continued doing poetry with a Master’s at San Francisco State, and basically I feel, to this day, that I am a poet. I have a poet’s heart, and a poet’s sensibility. When I teach creative writing I’m teaching people to know what a poet knows about language as a foundation for all of their writing. I tell them that the poets are the shaman of language, the ones who are most aware of the natural resources of language, its textures, its music, its spiritual aspects. I didn’t publish a book of poetry, though. I kind of went into other things. I got involved in community activism, then later I got pregnant, and was a single mother, and later I got together with someone and had another child. I really didn’t write, except for publishing some personal essays in the Chronicle related to my children, and the schools in San Francisco, teenage gun violence, things like that. I wrote a book, Journey Into Motherhood and basically became a mother. I was just teaching writing for a long time. And underneath I was aching to be the artist with language I knew I was. I needed a bigger canvas. And I’d had so many experiences by then, I’d traveled all over Asia, I’d lived in Italy for three years, I had friends from every background. I wanted to learn to write fiction, and I got into the MFA program at Bennington. I thought, oh, I’ve written poetry, fiction is going to be a breeze. And it was not. But once I did those two years, my learning curve went zooming forward. I got an award with one of those stories as soon as I left Bennington. I had just matured, and learned how to use my poetic sensibilities and love of language in a way that served the story. Early on, it was a little overwhelming, because I was more a woman of ideas and language than character and plot. So it took me a while to have my ideas and language be in service of the story. That's how it happened. Sue Well, at Stories on Stage you’ll have another chance to learn about your characters, and that is to hear someone other than yourself read your work. Have you ever had that experience, and how do you think you’ll react? Leslie I’ve never had that experience. I’m a strong reader of my own work, and so it’ll be fascinating to just be in the audience. When I read, I always have the audience close their eyes because so much of my stories are all about the sound, the music and poetry of the sentences. So I’ll get to be that person, to close my eyes and listen to someone else. And I know the stories so well, so I’m curious about how another person will feel the rhythm, and the musical scoring I’ve put there with the punctuation. I’ll be curious about how that person experiences it, feels it, and how I experience and feel it. I don’t know, I’m kind of scared. But it’s very exciting, too. Sue Are your family also writers? Or, just appreciative readers? Leslie They are appreciative readers. But my mother’s mother did get some poetry into the Saturday Evening Post, and my brother is a songwriter. And my sister doesn’t necessarily identify as a writer, but has secretly, in her own private world, enjoys writing about her life. Sue And now for the final fluffy question. Does everyone tell you that you look like Carly Simon? Leslie (laughs) Nooo. Sue Really, I’m surprised. Because the photo of you looking back with the big smile looks like the photo of Carly Simon on one of her albums, if I remember correctly. Leslie Yeah, I looked her up, and I can see that. But, I’ve usually been compared to Jamie Lee Curtis. Once a guy next to me at a traffic stop even opened his window and hollered at me, hey, does everyone tell you that you look like Jamie Lee Curtis? That’s the one I’m usually compared to. Sue Well, Stories on Stage Sacramento fans, you can decide for yourself when Leslie Kirk Campbell is featured on April 22. Is it Carly Simon? or Jamie Lee Curtis? And take a look at her website, with its links to some of her very fine essays, and also take a look at Ripe Fruit’s website. You might want to sign up for a class! Interview edited for length and clarity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

Who We AreLiterature. Live!

Stories on Stage Sacramento is an award-winning, nonprofit literary performance series featuring stories by local, national and international authors performed aloud by professional actors. Designated as Best of the City 2019 by Sactown Magazine and Best Virtual Music or Entertainment Experience of 2021 by Sacramento Magazine. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed