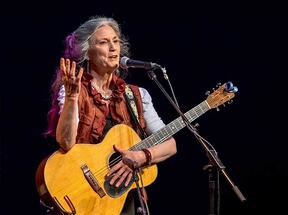

Author Sands Hall Author Sands Hall Sands Hall is a writer, musician, actor, and teacher, and for a long time, even those closest to her were not aware that for ten years she had also been a practicing Scientologist. Her time in Scientology, her ten years denying it, and how she finally found value in those “lost years,” is the substance of her fascinating memoir Reclaiming my Decade Lost In Scientology (Counterpoint Press.) I first met Sands when I took a writing course from her (and I highly recommend the one being offered by SoSS) and was thrilled when Dorothy and Shelley announced that she would be a featured writer for Stories on Stage Sacramento. Excerpts from the book will be read at the live, on-line event on July 17 (register here), but meanshile I jumped at the chance to interview her. I don’t know much about Scientology, except that it’s portrayed as a weird, dangerous cult by those who have “escaped” it, and as the solution to the world’s problems by those devoted to it. Which is it? As it turns out, for Sands Hall it was neither, exactly. In her memoir, she dives deep into the reasons she was attracted to Scientology, and is unsparing in her examination of herself, her famous literary family, and the benefits and dangers of a religion that demands so much of its adherents. Sands was, of course, her usual brilliant, generous and thoughtful self. She’s currently sheltering in place in Nevada City, and talked about the memoir, and how it came to be, during a recent exchange of emails.

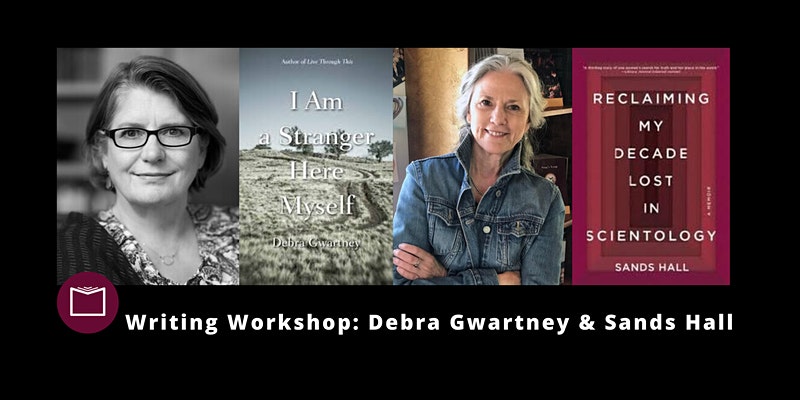

Now and again, even as I was urgently telling the students that this was an essential idea to take with them in their lives, I would cock an eye at myself and ask, “Hello, Sands? Maybe that trek through Scientology was such a journey,” and I’d scoff—"No! That was just a huge f-ing ERROR.” But little by little, I began to look at that idea more closely, and eventually, I began to write short pieces, and then longer ones, and I realized the model was a way to “reclaim” -- to find the “boon” within—of what, up to that point, I’d thought of as wasted, squandered years. Sue: Did it take you some time to discover the focus? Sands: The memoir started out to be much more about my brother. Its original title was PILGRIMAGE: My Trek Through Scientology and the Tale of a Brother. But, as is clear from the double whammy of the title (!), it was way too large and broad. On the re-re-re-rewrite, I figured out the Scientology command/phrase, “Flunk. Start.” was utterly apt. Once that became the title, it became clear that’s what I’d been writing about all along. (I should note here that Flunk.Start. was the original title of the book, changed when it came out in paperback to the current title, Reclaiming My Decade Lost In Scientology, because the publisher (Counterpoint) thought that Flunk. Start. sounded too much like a self-help book, which it definitely is not!) Sue: I have to say, this is the first memoir I’ve read that has extensive footnotes. They were fascinating, and I read every one. I really admire how careful you are to be fair to Scientology, to present all sides. Why did you choose to do that? It’s a memoir, after all - nobody expects accuracy, or footnotes. Sands: Thank you! In part, it’s due to a Scientological dictum that lodged in me fiercely; one of those that made sense to me. The idea that if you find yourself blaming or criticizing someone else for something, you’re almost always going to find that problem in yourself. So I wanted to make sure I left none of those particular stones unturned. In addition, there is—as I describe in the book—the whole idea of “Standard Tech,” Hubbard’s (L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology) insistence that you not decipher or explain or interpret for another. So I wanted to make sure that whenever I spoke about Scientology I offered the reader either Hubbard’s actual words, or a link to where those works could be found (at least at the time the memoir was published; so much is in flux within the Church right now!). Sue: You write about wrestling with Scientology’s insistence that you get rid of all negative influences. Your adored parents were particularly singled out as being “suppressive.” And there were times I found myself agreeing with this assessment. Intended or not, I saw parallels between the expectations of your parents and the expectations of Scientology – for both, that theirs was the one true way. Am I misreading this? Sands: This is a very smart and wonderful question. Absolutely I saw those connections, particularly as I was writing the book. But I wanted the reader to both side with me—my wonderful parents!—and to also cast a bit of a critical eye on the sort of “ownership” those wonderful parents seemed to exert on me (that I allowed them to exert on me). That was so very hard to shake—because, as I clearly say in the book, the Halls were a cult too (I say that jokingly, of course). I can imagine that I was a bit more open to the cult of Scientology in part because I was familiar with the tactics. Included in that is a very very strong susceptibility of the power of the patriarchy, and (as Jessica tells me early on in the book), I’m really (I like to think WAS really) susceptible to men who exuded power like that, especially intellectually. While one can argue that Hubbard was not intellectual, a lot of his ideas excited that kind of passion and curiosity in me—something else I try very hard to make clear in the memoir. In some bizarre way, I think I kept thinking that my parents woud be proud of all the thinking and studying I was doing. Ha! Sue: I imagine that this book, because it’s so searingly personal and unsparing, had to be very difficult to write. Were there times when you said “I just cannot write this?” Sands: Perhaps oddly, Sue, I never once thought “I cannot write this book” (although there were times when I was pretty sure no one would ever publish it — as one large publishing company back east told my agent, “There’s no scandal! We’re certainly not going to get any pages in PEOPLE magazine with this book, are we!”). I have a pilgrim soul, and in addition, all kinds of latent Protestant/Catholic thinking that pain is good for said soul. In fact, I think going in deep like that IS good for the soul. At least it was for mine. I got rid of so many false notions about myself and my family and my so-called “place in the world,” and “expectations.” It became very clear to me that even if the book was never published, the writing of it was worth every ounce of the time and energy and pain and work: I was indeed, as the title says, reclaiming myself. And not just (as the title also says) the decade lost in Scientology, but all kinds of years before that as well. Maybe in that case not reclaiming, but re-assembling. Sue: What did Scientology cost you? What did it give you? And, could you have had the tools to write this memoir without the training in self-examination you got from Scientology? Sands: Well, of course the ENTIRE BOOK answers that question! But the short answer: it cost me a decade of my life and the things that might have otherwise happened in that decade, including a larger acting career, and possibly a singer/songwriting one as well, and (I can’t help but think) marriage and children (that latter is still an ache, even though I very much appreciate what the lack of children has allowed me to do in my life). But of course that decade could have been filled with other kinds of horrors: a terrible marriage, screwed-up children (both of these I can easily imagine), too much drinking—I mean, the reason I was drawn to the cult in the first place was because of the answers it appeared to offer to a terrible emptiness in my life and in my soul. I write about how powerfully being told the rest of that Alexander Pope quote, Hope springs eternal in the human breast acted on me! ….: man never is, but always to be blessed… I mean, YIKES! That was a really horrid existential turning point for me.! And of course, as I say in the book those years gave me much, including helping to focus my passion for words. I know I became a better teacher—I could actually imagine myself as a teacher—because of my studies and training and work in Scientology. That was already in my bones; I was already teaching when I married Jamie, the man who “got me into” the Church; but I definitely learned a lot while in the church/cult that I applied to my teaching—again, as I say in the book, especially in the final chapter. And many other things. I think I was always an ethical person, but the whole “ethics” vs “morals” aspect of Hubbard’s writings was really inspiring. Sue: I imagine you’ve had many responses to the book from Scientologists and former Scientologists. Tell me one that was especially memorable. Sands: Probably the most beautiful one (I quote it—a text—in its entirety, although where I’ve underscored is what really moves me—exactly what I hoped the book would do): “This is why I think of you as a goddess: you create realities through your writing and music that invite, inspire, challenge, and heal others. FLUNK. START was good in all the ways I might have guessed from knowing you the little bit that I do, but I was surprised by the healing it offers! You gave me (literally) the possibility of having compassion for my own misguided pursuit of perfection and the shame of 'lost years.' Thank you, dear Sands! Wow wow wow! 24 hours from start to finish." On the other hand, from a friend who remained a Scientologist (and clearly never read the book): “You know you’ve cut the line to us.” The personal responses have been most gratifying. Just huge. Sue: What were your expectations/fears about publishing this book? And which of them turned out to be true, which untrue, and how do you feel about how it’s been received? Sands: I worried the “church” would come after me in some terrible way. They played some mischief on Amazon—tying up the book with copyright complaints, which were absolutely bogus, but to which Amazon had to pay attention—but other than that, they left me alone. Thank GOD. Sue: So it’s really interesting to me that you earlier referred to yourself as a “pilgrim soul.” Because as I was reading the book and preparing the questions I kept thinking of you as a pilgrim, and as you did in your Scientology studies (and I’m sure still do) I looked up the word pilgrim. It’s Middle English, meaning “seeker” but the root is the Latin word meaning “foreigner” – a slight shift I find pretty wonderful. Did you know this? And, do you feel you’re a foreigner, in a way?  W. B. Yeats Irish poet and playwright 1865 - 1939 W. B. Yeats Irish poet and playwright 1865 - 1939 Sands: I love Yeats’ beautiful poem-- When you are old and grey and full of sleep, And nodding by the fire, take down this book, And slowly read, and dream of the soft look Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep; How many loved your moments of glad grace, And loved your beauty with love false or true, But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you, And loved the sorrows of your changing face; And bending down beside the glowing bars, Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled And paced upon the mountains overhead And hid his face amid a crowd of stars. —And that idea of a pilgrim soul has long been with me. I wrote an entire essay on the etymology of the word, and what a pilgrimage means (not so much the destination but the journey), and I’ll attach a short version of that (link provided below). I’ll also try to remember to attach the song I wrote about the time I finished the first draft of the memoir, which starts:  Sands Hall Sands Hall It’s been a Pilgrimage Season I have been lost on my way Now I’ve found my way back to the place I started How can this be Where in the world…? Listen to Sands' beautiful song, "Pilgrimage Season," off her album Rustler's Moon. Yes, to the foreigner question. I always felt that, actually, and one of the strange and wonderful blessings of writing my memoir is that I don’t feel that any more. Although I remain a pilgrim. And so back to the hero’s journey with which these questions began… At the end of his essay, “The Self as Hero,” Joseph Campbell writes that he thinks “a well-lived life is one hero’s journey after another.” I agree with that. Let’s always be ready for the next challenge, and the next adventure, and be aware that the underworld, while scary and dark and sometimes seemingly endless, holds incredibly important pieces of illumination that we can bring back with us when we return. Thank you for the excellent “conversation,” Sue! Sue: The pleasure was mine! Here's a link to a wonderful recorded Interview with author Sands Hall, by Betsy Fasbinder. Here's a link to Sands' excellent essay, "Light a Candle" on the LA Review of Books Blog (10/13/2019), and to a recording of her song "Light a Candle for Freedom" (also from the album, Rustler's Moon). And, lastly, here's a PDF of the short version of Sands' essay, "Pilgrimage," referred to above. Join authors Sands Hall and Debra Gwartney for a Stories on Stage generative writing workshop! Sunday July 19, two sessions - 9 to noon, and 1 to 4 pm - only $50.00

Writer, Sue Staats Writer, Sue Staats Sue Staats is a Sacramento writer. She directed Stories on Stage Sacramento for six years, from 2013 to 2019, and now contributes interviews and blog posts to the website, and cookies to the events. She’s currently looking for a home for her short story collection and getting her feet wet in a couple of other projects, with the hope that eventually one of them will draw her into deeper waters. Sue's fiction and poetry have been published in The Los Angeles Review, Graze Magazine, Farallon Review, Tule Review, Late Peaches: Poems by Sacramento Poets, Sacramento Voices, and others. She earned an MFA from Pacific University, and was a finalist for the Gulf Coast Prize in Fiction and the Nisqually Prize in Fiction. Her stories have been performed at Stories on Stage Sacramento and Stories on Stage Davis, and at the SF Bay-area reading series “Why There Are Words.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

Who We AreLiterature. Live!

Stories on Stage Sacramento is an award-winning, nonprofit literary performance series featuring stories by local, national and international authors performed aloud by professional actors. Designated as Best of the City 2019 by Sactown Magazine and Best Virtual Music or Entertainment Experience of 2021 by Sacramento Magazine. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed