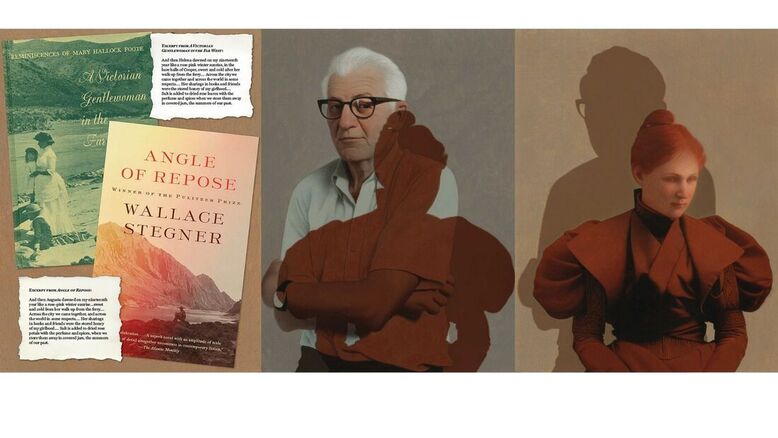

Taking on Giants--Sands Hall's Decades- Long Quest to Establish the True Heroine of Wallace Stegner's Novel Angle of ReposeAn interview by Sue StaatsIt’s not an easy task, going toe to toe with literary greatness. A well-established giant of American letters, Wallace Stegner is best known for his novel Angle of Repose, which won the Pulitzer Prize and is considered a cornerstone of American writing. Yet Sands Hall takes him on fearlessly, no holds barred. Her latest salvo, a powerful essay just published by Alta Journal, “The Ways of Fiction Are Devious Indeed,” is an engagingly written, thoroughly researched, and very personal excavation of the plagiarism in Stegner’s novel. A section of it will be read at Stories on Stage Sacramento on Friday, May 27. The essay, linked here, is the result of some twenty-plus years of digging, rumination, and writing. I was curious to know how the story began, and what Sands hoped to accomplish by bringing the information to light. Sue: Sands, how did your entanglement with Stegner’s novel Angle of Repose begin? What was the spark that set off your journey to recover Mary Hallock Foote’s true story? Sands: Well, the theatre company I was involved with at the time, Foothills Theatre Company, had a very visionary director, Philip Sneed. And he had this idea about making Angle of Repose into an adaptation, which made great sense, because we’re here in the Grass Valley/Nevada City area, and the book’s narrator, Lyman Ward, lives in Grass Valley, and the protagonist, Susan Ward, moves to Grass Valley at the end of the book. So it just made sense. It’s a great novel that many, many people know and love. And then, as we were looking into it, Tom Taylor, who was my sweetheart at the time, said there’s this local animosity aimed in Stegner’s direction. Did he steal someone’s journal? And I just pooh-poohed it, utterly. But then the director of the project actually gave me a copy of Mary Foote’s reminiscences, which I dutifully waded into, and within minutes I was like this is really weird, I just read all these passages, I know these people already. And it was then that I got all excited and went down to Stanford for more research. That was the genesis. I thought, oh my god, maybe there is something here. Sue: So you did a lot of research at Stanford, and you spoke with your father about it (Oakley Hall, novelist and friend of Stegner’s). What was his response to what you'd unearthed? Sands: I’d never been a scholar. I’d never used the library like that, where you go and order materials and you sit and they bring you boxes from deep in the archives somewhere and you have to wear white gloves and handle all this stuff. It was very new to me. My mother and father were living in San Francisco at the time, and I stayed with them. I was down there I think three or four days, and of course talk circled around what I was in the process of uncovering, and when I told my dad, he actually brought up his own novel Warlock, which had been nominated for a Pulitzer, and he said that his editors had assumed that the journals he had written that are ascribed to a guy named “Goodpastor,” a character in the novel, and they said you can’t just use someone’s journals and he felt very smug and excited that they thought he had borrowed them, that he’d gotten the voice so right. But he just didn’t seem to have the proper degree of outrage and dudgeon that I thought he should have (about Stegner lifting entire paragraphs of Foote’s work and using them without attribution). And when I said, "why are you almost defending him Dad," he said to me, “The man was my friend.” I remember being so struck by the many aspects of the profundity of that. That he felt that degree of affection for his friend, and also I was a little bit shocked and surprised that the friendship would keep him from being more outraged. And yet as the years have gone by I have respected the friendship. But that line definitely resonated with me. Sue: Your parents are both gone now. And I’m wondering if you would have written, or published, this essay if he, and that generation, had still been with us. Sands: Oh, absolutely. One of the things I want to make absolutely clear is that they were completely supportive of the work I was doing. He handed over books, and biographies, and all kinds of material on Stegner which were extremely useful to me. When I came to write the play Fair Use, which was the first outing I gave to this scandal, I named a character WS, conveniently, which is quite similar to a character named Wallace Stegner. That character, WS, got to say some really, really good things about writing, some of which were from my dad. There’s also a character named Historian, who’s Playwright’s father, and their relationship, that they can talk about, and get upset about plagiarism, and borrowing from others, was very much based on my relationship with my father, even though the two characters are very, very different. Yes, I borrowed a lot from, basically, our friendship. They would have applauded this being published in Alta Magazine, they would have been thrilled in every way for me. Sue: It’s wonderful that you were able to mine this experience in that way. I can’t help but wonder, if we were to transfer Wallace Stegner and Mary Foote into today, how the current atmosphere of people being excoriated for past behavior would have affected Stegner—legally, morally, and in terms of his reputation. Sands: Well, it’s a great question. Foote would be dead, of course, but her letters and reminiscences would be available. But I would like to think that it would not have occurred to a writer now to have used these things so indiscriminately. There was a fascinating talkback after one of the productions (of Fair Use) that was performed up in Boise, Idaho. A woman said that Stegner, when he published Angle of Repose, could not have imagined that women’s diaries would start to be mined for the most arcane details. So that Mary Hallock Foote, being an extraordinary writer, and having catalogued her extraordinary experiences, including with a husband who was a mining engineer, and that she published short stories and novels and essays and published her reminiscences and wrote endlessly to her friend Helena back East, that all of that was just extant, readers didn’t have to go looking for the little clues. And also, partly in answer to your question: Stegner was born in 1909—women didn’t even have the vote—so there was an enormous amount of change that he saw in his lifetime, and in my opinion his novels really reflect a very fifties, forties view of women in general. I just that think that even naming Mary Hallock Foote “Susan” has that kind of feeling; it’s just a very fifties sort of name. Sue: Right (laughs). But it makes me wonder if he thought, well, it’s just a woman’s diary, a woman’s piece, I can get away with lifting whole bits of it. And nobody will think any the less of me, and I will just be able to get away with it, because I matter more than she does. Sands: Yes. And he said—I don’t have this quote exactly in front of me, but he said, “She wasn’t interesting enough to put a novel around her. By fictionalizing her, I made her immortal.” Sue (stunned silence): Well I guess we have to thank him, or something. Sands: People have posted—because this has gotten a lot of play on social media—one person wrote and said, “Well, I will just point out that nobody would have known about Mary Hallock Foote if it wasn’t for Stegner’s novel.” I had to write back and say, "First of all, history on that hasn’t been written yet, and second of all, I don’t think that’s true. Because people have discovered her, and I wouldn’t be surprised if one or two of her novels aren’t reissued, because they are very interesting in their own right." Her novels are of a time, you can feel it, as Wallace Stegner’s are of his time, there’s a style. But she plots very well, she has wonderful characterizations, her descriptions are fabulous. I don’t know if we’re only hearing about Mary Hallock Foote because of the scandal around Wallace Stegner’s use of her. Sue: A friend of mine told me of her husband’s reaction to the essay: he said, "Oh, it’s historical fiction, everybody does that, so what." And I’m wondering if you’ve seen a difference in the way women see this essay, which is essentially about a man appropriating a woman’s life, and men see this essay as being, oh, it’s something that just happened. Sands: I do think it falls down gender lines in a way that’s really, really intriguing to me. Pam Houston shared the essay on Facebook, bless her, and there was a lot of response to it. There were three or four comments of the sort, “It’s a great book, doesn’t matter, he was within his rights,” and a few others like that, and someone else came along and said, Listen, old white guys posting these really disparaging comments: first of all it’s really obvious that you’re old white guys, and second, why don’t you read the essay before you comment.” I think this is important because what I try to say in the essay is that is does matter that Stegner felt their lives weren’t interesting enough, because in fact they broke their hearts, and their backs on this dream of bringing water to Boise, and they came out with no money and very little pride, and then the US government took that vision of Arthur’s and made it happen. Maybe that truth doesn’t finish out Mary’s life so marvelously, but it does finish out their married life in a way that moves me, and was an opportunity Stegner wasted. So when your friend’s husband says it’s just an historic novel--the big difference there is that Stegner followed her life so precisely for most of the book, and then twisted it so inelegantly and unfairly that people here in Grass Valley assumed that there was lots of true stuff, that Stegner had told the real story. Sue: The part at the end of the book, which involves an affair and the daughter’s death and Oliver never speaking to Susan again? Sands: Right. So in real life, Mary’s daughter died of tuberculosis, but the people in Grass Valley thought that Mary had an affair (in the book, Susan has an affair and neglects her daughter, who drowns.) They also thought that they were so hoity-toity out there at the North Star (Stegner renamed it Zodiac) mine and house, and not mixing with the locals, and because of the book, they thought it was because they weren’t talking to each other (in the book, after the affair, they don’t speak for the rest of their lives.) Lots and lots of people felt that thing in the community (that how the book ended was the real story of the Footes.) But to me an historical novel is this: you’re taking a person’s life, and you might change some details, like Gore Vidal did with Lincoln. Vidal uses the point of view of Lincoln’s secretary, but he’s telling Lincoln’s life and he doesn’t twist the biographical details. And that’s where I think the error is. It’s not historical. Sue: How do you think Stegner should have handled it? If he was going to use someone’s life word for word, why didn’t he own up to it? Because the whispers of plagiarism started early, right after the book’s publication. Sands: Well—I imagine him typing word after word into his manuscript, because I was doing so much of that writing the play—I was typing their words, word after word. Adding all the attributions, so the audience would be very clear whose writing was whose, added five minutes to the length of the play, so there’s that. But I think he just made a devil’s bargain, and it’s why I think he says, in one of those final letters to Janet, “Great, wonderful, I feel like a character in literary history.” I do think he wondered if it would catch up to him. Maybe I give him too much credit for that. But I do wonder. That statement, to me, says “I’m a character in literary history” not because his novel was going to be this big best-seller, which he didn’t know at the time, but because, I think, he thought that no one would find out. I have to make this deal, he thought. He'd borrowed so much, that to have to go back in and write himself what he’d borrowed from Foote, the actual lifted verbatim passages, how hard would that be? How do I change the arc of this amazing life which I have borrowed hook, line and three quarters of sinker—I mean, there was this much (fingers pinched nearly together) he didn’t borrow. So, how should he have handled it? By making it a novel about Mary Hallock Foote and her husband. Sue: Better. He should have handled it better. Sands: Right. Sue: The dedication is to “JM and her sister.” Through your essay, I discovered that JM is a grandchild of Mary Foote. So is that, in a small way, acknowledging Mary Foote, do you think? Because she’s not acknowledged anywhere else. Sands: Well, as he says in one of his letters, “I had to thank them rather darkly and ambiguously.” And here’s the thing—I don’t get into this, because it’s the excuse he offers endlessly. He writes the family, and says, “Do you want to read this big fat manuscript? It’ll take about a week.” And they’re all excited, they’re talking to Stegner! They’re thinking of course, we’re excited to read what you’re going to come up with about our family, you’ve had the reminiscences, you’ve borrowed the letters, this is going to be so fun to read! And then he got the news that the reminiscences were going to be brought out by the Huntington Library Press. And they were going to come out within months of his novel, unless he got a move on. So all of a sudden this stuff that no one knows, this manuscript that no one’s read, is going to be in the public eye. “Will it take a Foote scholar to find the facts behind my fictions?” he writes. So at that point the sister Janet appears to write back and say, or at least he says she said, “Well then, change the names of the family.” Why he feels that’s going to solve things, I don’t know, but that’s what he did. So he goes back and changes Mary to Susan, and Arthur to Oliver, Bettie to Betty, Lizzie to Lizzy. I mean, he just didn’t even try. And Agnes he doesn’t change at all. So that was his excuse, and the dedication includes the phrase, “This is in no sense a family history.” And of course, seven-eighths of it is completely family history. Sue: So, do you see any parallels between Stegner’s misuse of Mary Foote’s life and some of the ways current stars, politicians, even writers have misused their power? And how they’ve been discovered, and punished for it by loss of status? I mean, Stegner isn’t guilty of sexual misconduct, it’s more of a literary mistreatment. But it’s the misuse of a life, and do you think Stegner’s reputation deserves similar treatment? Sands: Treatment as in? Sue: Diminishment as a literary figure. Sands: Stegner’s biographer Jackson Benson writes that Stegner always seemed to need a story on which to hang his books. He cites some examples, and Angle of Repose was one of them. The difference was that he used so much verbatim material (in Angle of Repose). I have read in several places that when he published Crossing to Safety he was so worried about what had blown up around Angle of Repose that he got in touch with the family he’d based the novel on, and the kids of that family, and actually had them read it and got their okay. It’s different, it’s so different. You know, people have said the Pulitzer Prize should be rescinded, the Stegner writing program (at Stanford University) should be renamed, etcetera. I don’t think that’s ever going to happen. The reason I decided to bring this information newly to a lot of readers who loved that book, or who didn’t, is because I wanted to bring this misbehavior to a newer audience. Academics have known this for years. Angle of Repose is the novel for which Stegner is most well known, and it does feel appropriate to bring attention to what he did to create that novel, which was really, really incorrect. It was wrong. Sue: What do you hope will be the outcome of people reading and discussing your essay? Because it has blown up, possibly more than you expected, and created a lot of conversation. I think that might have to do with some of the discussion around appropriation today, but I wanted to ask what you would like to, ultimately, come of the information you newly bring to attention? Sands: It’s very similar to what drove me to write the play: I wanted to right this wrong. I wanted Mary Hallock Foote to get some significant credit for the character that she actually was. Susan Ward, I think, is made kind of measly—but the arc of that amazing life is there, and that is one that the Footes created. Mary Foote’s own writing is vivid and fine and you just read phrases and say, Oh! That’s so lovely!. Stegner’s dedication does say thanks to the Foote grandchildren for the loan of their ancestors – but it’s not borrowed, it’s stolen. And I want that to be as clear as possible. You know, my editor—the wonderful, wonderful Mary Melton (and by the way, they’re doing a webinar May 25 ( signup info here ) asked a very similar question—what made you write the play? And I remember writing that paragraph for the essay in a white hot heat, looking into this issue. Of course, I’d been aware for ages of men borrowing women’s work, and how Christianity and God and all of the Judaeo-Christian putting women in their place stuff, and writing it I became fixated onto “look at what men do to women all the time.” That’s not exactly fair, because lots of men do wonderful things for women. I mean when women got the vote, it was all men who had to vote for it. But lots of times there’s this terrible old fashioned way of thinking. One woman wrote me and told how her father had said that in his youth, they believed that women were inferior beings. It’s the issue of all marginalized folk, they’re not considered as good as white Christian men. And it’s a very, very relevant problem. Sue: Any difference you can make is an important one. Sands: Absolutely. If I can just drop a little more water in the pond, push that discussion a little more forward, convince one more person to see something differently, then that’s worth all of it. Sue: One last question. You’re an actor as well as a writer of essays, plays, fiction and non-fiction, and you’re an excellent reader of your own work. I’m wondering if you’re looking forward to sitting in the audience and listening to another actor read your words. Sands: Oh, I so am. Having an opportunity to have a section of my memoir read by Kellie Raines—I mean, there was a moment where I thought, well, I can read it. But it was on Zoom, and she used Zoom really well and I was thrilled. I mean, how fun is it? And Meagan’s a wonderful actor, and we know each other, and I’m really looking forward to it. There isn’t characterization, but there is a stance in this essay and I’m looking forward to seeing how she takes it on. Sue: Thank you! Edited for clarity and length Sue Staats is a Sacramento writer. She directed Stories on Stage Sacramento for six years, from 2013 to 2019, and now contributes interviews and blog posts to the website, and cookies to the events (when they aren't virtual). She’s currently looking for a home for her short story collection and getting her feet wet in a couple of other projects, with the hope that eventually one of them will draw her into deeper waters. Sue's fiction and poetry have been published in The Los Angeles Review, Graze Magazine, Tulip Tree Review, Farallon Review, Tule Review, Late Peaches: Poems by Sacramento Poets, Sacramento Voices, and others. She earned an MFA from Pacific University, and was a finalist for the Gulf Coast Prize in Fiction and the Nisqually Prize in Fiction. Her stories have been performed at Stories on Stage Sacramento and Stories on Stage Davis, and at the SF Bay-area reading series “Why There Are Words.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

Who We AreLiterature. Live!

Stories on Stage Sacramento is an award-winning, nonprofit literary performance series featuring stories by local, national and international authors performed aloud by professional actors. Designated as Best of the City 2019 by Sactown Magazine and Best Virtual Music or Entertainment Experience of 2021 by Sacramento Magazine. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed